On February 8, the Institute released a new report, Canada’s Net Zero Future, examining pathways to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 in Canada. This blog takes a closer look at what achieving net zero means for economic growth. We find that growing the economy is absolutely consistent with a net zero future in Canada. We also share insights from our research about where some of the biggest challenges on the way to net zero might lie—and what Canada can do about it.

Canada’s economy grows in every net zero scenario

Economic growth is usually tracked in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), measuring the total value of goods and services produced in a country in a given year. While GDP doesn’t capture all aspects of economic well-being by any stretch, it still provides useful insights, especially in combination with other metrics. Economic growth isn’t just some abstraction—it reflects jobs and income for Canadians.

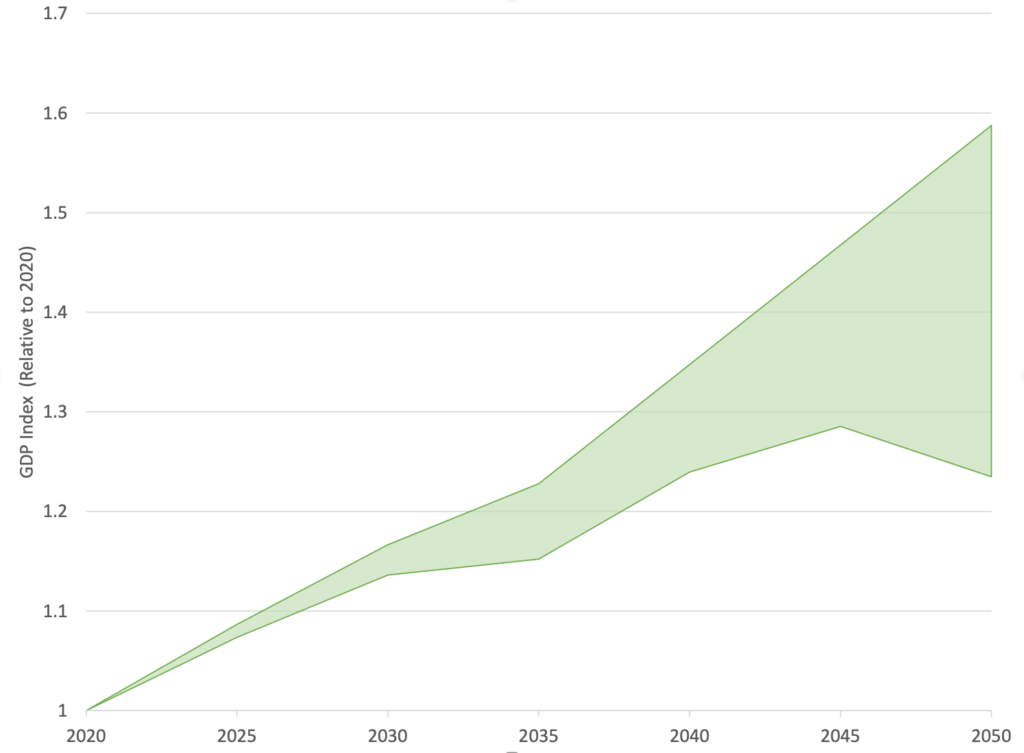

Our study examined more than 60 possible pathways to reach net zero by 2050, and in all of them Canada’s GDP is substantially larger than it is today. As the figure below illustrates, the economy continues to grow on the way to net zero. Canadians’ incomes are expected to rise.

Figure 1: Projected changes in Canadian GDP across 60+ net zero scenarios

The figure shows the full range of projected (real) GDP growth from 2020 to 2050 pathways across all our scenarios. As the figure illustrates, the range of GDP projections widens as we move farther into the future. This isn’t so surprising: it’s challenging to project economic growth two years out, let alone 30.

Notably, these numbers underestimate potential future growth, because they exclude a host of benefits that come with a net zero transition, such as reduced health costs due to cleaner air and less traffic congestion. Our modelling also doesn’t capture potential growth of new, emerging sectors producing products which don’t yet exist (but which might be big drivers by 2050)—30 years ago, we couldn’t have conceived how a digital economy would look today. Still, new studies that better represent the full range of benefits of climate action are showing even smaller GDP costs and even larger GDP gains from ambitious low-carbon transitions.

The last step is the hardest

In the figure above, one data point in particular emerges as the exception to that trend of economic growth. At the very low end of the range of projections, a few scenarios actually show declines in GDP from 2045 to 2050. In other words, a few pathways to net zero imply a contraction of the Canadian economy in the homestretch. These more pessimistic scenarios raise some interesting flags and generate some useful insights that can help Canada avoid that outcome.

That potential dip in the curve in 2045 illustrates that reducing the final few megatonnes of emissions from the Canadian economy will be particularly challenging. By 2045, all the low-cost opportunities to reduce emissions have been tapped, and only the expensive reductions remain.

Those reductions will be particularly expensive if we don’t see big breakthroughs on some game-changing technologies. All scenarios with significant GDP costs in 2045 to 2050 share a key assumption: they all assume that most “wild card” solutions (i.e., technologies that aren’t yet commercially viable) do not ultimately prove scalable and cost-effective in Canada. In particular, the absence of negative emission solutions—used to remove and permanently store carbon dioxide, through technologies like direct air capture and carbon sequestration—is an important factor in those pessimistic scenarios. The absence of other wild cards, such as second-generation biofuels or hydrogen networks, only exacerbates the challenge.

Moreover, Canadian policy choices can affect the likelihood of wild cards being available. It can support innovation in a range of ways, from public investment to pricing carbon. The GDP results here further emphasize the potential benefits of doing so, especially in the homestretch of our net zero transition.

But how likely is this outcome? In the report, we’re careful to note that putting all of our eggs in a wild card basket is a risky strategy; we can’t ignore the safe bets. Yet on the other hand, assuming that most wild card solutions will prove unavailable is overly pessimistic. For example, even if they aren’t available at scale, the use of negative emissions solutions on a more limited scale might very well be available to avoid the most expensive emissions reductions on the way to net zero.

Hedging our bets in a global policy transition

Our analysis clearly shows that Canada’s future net zero economy will be stronger than the economy of today. Canadians will be better off. And when the other benefits of the transition are taken into account—from falling energy costs to cleaner air and better health to avoided impacts from a changing climate—they will likely be much better off.

That doesn’t mean we can take a prosperous net zero transition for granted. It will take a dedicated and concerted effort. And while not all forces influencing our path to net zero are within our control, many are. If we manage the economic risks of the transition carefully, we can lay the groundwork for a growing economy—and shrinking emissions—to 2050 and beyond.

You might also like…