Summary Statement

Canada’s federal government should adopt a whole-of-government approach to climate change. Such an approach can leverage executive leadership to encourage cross-departmental collaboration and integrate climate change into all of government policymaking. Canada can learn how to establish an effective whole-of-government approach from the successes and challenges of its peers both at home and abroad. This brief examines whole-of-government approaches to climate change from around the world as well as specific lessons learned from three case studies—the United Kingdom, the United States, and British Columbia.

Executive Summary

Climate change is a complex, cross-jurisdictional issue that requires societal transformation. To meet this challenge, governments must be able to make climate policies that work across sectors, communities, and regional borders. A whole-of-government approach can help to mainstream climate change into policymaking processes.

A whole-of-government approach consists of both governance structures (distinct organizational groups within government that are dedicated to cross-governmental coordination and collaboration, such as cabinet committees) and processes (rules, standards, or mandates that direct at least two departments’ policymaking and policy implementation).

Effective climate policies that get Canada where it needs to go will require the active involvement of departments as disparate as Finance, Infrastructure, Transport, Natural Resources, Environment and Climate Change, Agriculture and Agri-Food, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Employment and Social Development, and others, necessitating a coordinated approach to ensure coherent implementation of climate strategy.

Whole-of-government approaches to climate change have become a feature of some national and sub-national governments over the last several years, as countries commit to increasingly ambitious measures to curb their greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to climate change, and pursue clean growth strategies. An integrated, coordinated, cross-department approach can leverage departmental expertise, reduce policy redundancies, mainstream climate change into all decision making, and create cross-departmental synergies for more effective climate governance.

In this paper, eight countries were surveyed to identify whole-of-government structures and processes dedicated to climate change, and three of these cases (the United Kingdom, British Columbia, and the United States) were analyzed in depth to determine the benefits and risks of such an approach.

Of course, not all whole-of-government approaches are created equal. In theory, a whole-of-government approach can leverage public-sector expertise across departmental boundaries to increase climate ambition. In practice, this approach can be difficult to implement. On the one hand, establishing well-resourced structures and processes to foster inter-departmental collaboration can lead to more effective climate policy. But competing interests within government, and constraints on financial and human resources, mean that a whole-of-government approach is not easy to maintain. In support of finding that balance, there are five lessons to be learned from the cases examined here for implementing a cohesive and effective whole-of-government approach to climate change:

- The success of a whole-of-government climate initiative depends on sustained executive leadership directing departmental priorities and inter-departmental coordination.

- An effective whole-of-government climate initiative requires adequate funding, a clear mandate, and capacity to enact change across departments.

- An effective whole-of-government climate initiative requires effective and empowered personnel acting in whole-of-government structures.

- The mandates of participating departments must align, or be brought into alignment, with the mandate of the whole-of-government climate initiative.

- A whole-of-government climate initiative should report publicly on its progress and be as transparent as possible about its deliberations, findings, and research.

1. Introduction

1.1. The whole-of-government approach

Climate change is a complex and urgent issue that requires a coordinated government response. Historically, climate change policy has fallen under the auspices of environment departments, while most other departments engage with it only as it affects their overall mandate and priorities. But in order to respond to the climate emergency quickly and effectively, governments must be able to mobilize the full breadth of their policy expertise to implement climate policies that work across sectors, communities, and regions.

The whole-of-government approach, which works across vertically organized departmental silos to encourage cross-government collaboration, is one approach to leverage that expertise. The approach sees government departments working together to solve complex issues like climate change that cross departmental boundaries (Christensen & Lægreid 2006).

As the Australian Management Advisory Committee’s Connecting Government (2004) report defined, “whole-of-government denotes public services agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues. Approaches can be formal or informal. They can focus on policy development, program management, and service delivery.” Often, the whole-of-government approach manifests in creating high-level inter-departmental committees that share information and collaborate to implement legislation and government mandates. Most times, these groups are under the jurisdiction of executive offices (e.g., Cabinet Office, Office of the President), which results in stronger and more effective central leadership.

The historical precedents for inter-departmental coordination on complex and urgent issues date back at least to the Second World War. The war committees and cabinets established in Canada in the 1940s saw high-level interdepartmental cabinet committees directing and sustaining a co-ordinated emergency response across government (Klein 2020). The formalized whole-of-government approach, however, emerged in the mid-1990s, when some governments shifted focus from disaggregated, single-issue departmental governance and towards a more integrated approach to complex issues that cross jurisdictional and departmental boundaries (Christensen & Lægreid 2007). The shift was most significant initially in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, but has gained popularity in other countries like the United States.

This paper will proceed with an overview of the characteristics of whole-of-government approaches, focusing on the use of inter-departmental committees and high-level government mandates, and then will present three climate-specific case studies: the United Kingdom, which has created several new cabinet committees to support inter-departmental coordination on climate; the United States, which has recently established the high-level National Climate Task Force; and British Columbia, home of the Climate Action Secretariat.

1.2. Characteristics of whole-of-government approaches

In a survey of international cases, we find that there are several characteristics that define the whole-of-government approach to climate change. These characteristics are listed for eight global whole-of-government approaches in Section Two and evaluated in depth for each of the case studies (the United Kingdom, British Columbia, and United States) in Sections Three through Five.

1.2.1. Whole-of-government structures to address climate change

Whole-of-government structures are distinct organizational groups or bodies that are dedicated to cross-governmental coordination and collaboration, including cabinet committees, task forces, and working groups (Christensen & Lægreid 2007; Verhoest et al. 2007). Multiple whole-of-government structures can exist simultaneously within governments. These are separate and specific forums for inter-departmental coordination on climate issues. Examples include cabinet committees dedicated to climate change or new offices under executive leadership (such as British Columbia’s Climate Action Secretariat or the United States National Climate Task Force). In whole-of-government structures, a clear mandate and involvement of the highest levels of leadership are crucial to success

To dig into that point specifically: A clear mandateis crucial to the success of any whole-of-government initiative. Interdepartmental committees’ authority depends on their ability to create new forums for collaboration and compel participation. Is their function primarily to share information and coordinate, or do they have some ability to collaborate in the development of integrated strategies, plans, and policies? Some whole-of-government structures are centrally located in the executive office, which allows for top-down pressure across departments and helps centralize climate action. Others are smaller, led by one department which relies on lateral pressure on its counterparts to affect change. Whatever its makeup, a clear mandate will help ensure an initiative’s success.

The membershipof these structures is also key to their success. Executive leadership decides on departmental membership in these whole-of-government groups and where they fit in the reporting structure. For instance, some groups may have a smaller membership and work on a narrower issue area, while others involve a bigger, more inclusive cross-departmental group with a broad mandate to address climate change across all areas of responsibility. Smaller groups are best suited to addressing specific initiatives that require only a few departments’ input, like enhancing disaster response to growing wildfire threats. Larger structures are useful for coordinating overarching climate action and tackling more complex issues like developing a national climate resilience strategy.

1.2.2. Whole-of-government processes

Whole-of-government processes are rules, standards, or mandates that direct at least two departments’ policymaking and policy implementation (Meadowcroft 2009). In the context of climate change, these processes prioritize climate change for every government department, even when there is no explicit structure for inter-departmental coordination. These processes are mostly used to direct an explicit assessment of climate change in departments that would otherwise consider climate a peripheral issue for their mandate, or to assign financial and human resources to climate action.

Procedural mechanisms include mandate letters or executive orders to Ministers or Secretaries that instruct cross-departmental collaboration on core government goals (like a government-wide net zero strategy). Legislation that requires integration of climate change into decision making (like Denmark’s 2020 Climate Law, which requires a climate assessment in every new piece of legislation) can also act as whole-of-government processes.

1.2.3. External advisory bodies

Independent climate advisory bodies are an effective mechanism for supporting whole-of-government climate initiatives, providing sound policy advice on climate change-related issues (Meadowcroft 2009). Such advisory bodies have benefits beyond whole-of-government approaches: they provide independent analysis of climate plans and go beyond government mandates to ask tough questions and help advise the government on policy decisions.

External advisory bodies often report to cabinet committees, the legislature, or the executive office as opposed to a single department. This helps keep climate change front and centre in all policy discussions. Where there is a relationship with whole-of-government structures like cabinet committees, external advisory bodies can help shape inter-departmental coordination on climate change as well as provide sector-specific advice. Their findings are often publicly available, providing a benchmark with which to measure policy outcomes from other whole-of-government mechanisms. Advisory bodies can ask questions that push for more ambitious and effective policymaking. They can help set both interim and long-term goals, provide policy advice, and ensure continuity through changes in government.

2. Survey of global whole-of-government climate change approaches

Whole-of-government approaches to climate change have become a feature of several national and sub-national governments over the last 20 years as countries commit to increasingly ambitious measures to curb their greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to climate change, and pursue clean growth strategies. Here, we survey a selection of whole-of-government approaches. Many of these countries have only recently given climate change whole-of-government recognition, with a few exceptions. Singapore has had several task forces and working groups dedicated to climate issues since 2007 (National Climate Change Secretariat n.d.). France was one of the earliest creators of an inter-ministerial forum for climate change in 1992, but that forum was absorbed into the Department of Ecology, Energy, Sustainable Development and Spatial Planning in 2008 (Bardou 2009).

This table provides a high-level overview of whole-of-government structures, processes, and external advisory bodies.

3. Case study: United Kingdom

3.1. Context

Due in part to the relative consensus on the need for climate action across parties, climate governance in the United Kingdom has been comparatively ambitious in the last two decades, with the near-unanimous passage of the 2008 Climate Change Act. However, weak coordination and lukewarm uptake of specific climate goals across departments has made implementation uneven and unstable (Lockwood 2021).

The structure of the United Kingdom government can keep policy issues siloed, as each department is ultimately responsible for issues under its portfolio. For instance, the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy is the department responsible for climate change, although other departments have been directed to integrate climate action to varying extents as a part of a whole-of-government approach (Dray 2021). The 2008 Climate Change Act requires net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, as well as shorter-term five-year carbon budgets to guide policymaking to achieve the 2050 target. Accomplishing these goals requires coordination across government departments, especially with cross-cutting issues (for instance, transportation, which requires input from multiple departments like Transport, the Treasury, and International Trade in addition to the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy).

The Prime Minister has the authority to create whole-of-government structures like cabinet committees or task forces and to decide on their jurisdiction and membership. Whole-of-government structures can be helpful because they allow for flexible responses to specific issues, and do not always require legislative consensus. However, because they are largely established by the executive, they can be disbanded easily by successive governments. As such, whole-of-government structures in the United Kingdom are based on the sitting Prime Minister’s commitment. This reliance on executive leadership is common among whole-of-government approaches.

3.2. Whole-of-government structures for climate change

The United Kingdom has had a spotty history with defining climate change as a whole-of-government issue. In 2006, the inter-departmental Office of Climate Change was formed “to work across Government to support analytical work on climate change and the development of climate change policy and strategy” (National Archives 2008). The Office was absorbed into the (then) Department of Energy and Climate Change in 2008, and the United Kingdom did not establish another whole-of-government structure specifically for climate change until 2019.

3.2.1. Cabinet committees

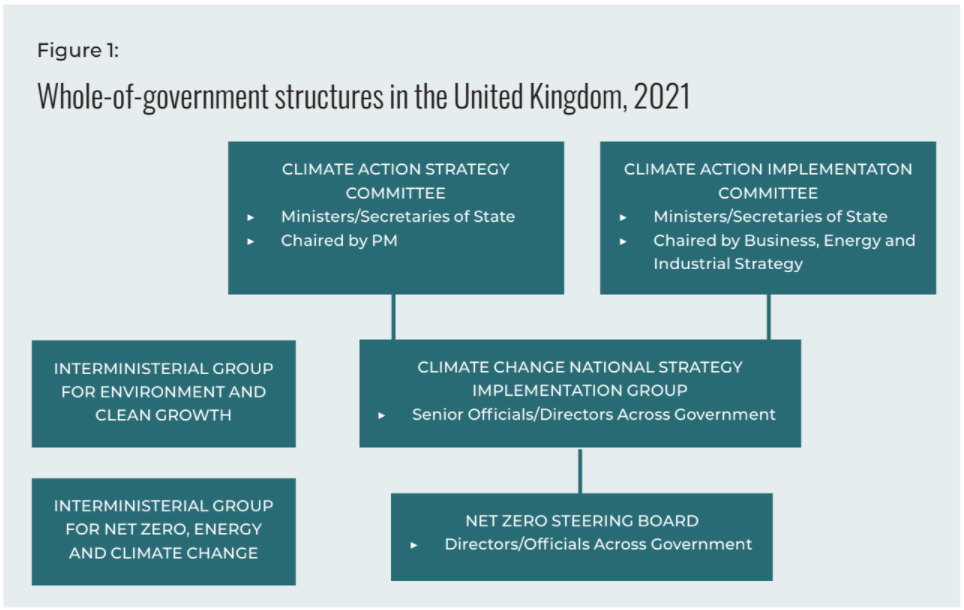

In October 2019, Prime Minister Boris Johnson created and chaired the Cabinet Committee on Climate Change. In June 2020, the Prime Minister split this committee into two: the Climate Action Strategy Committee and Climate Action Implementation Committee (Institute for Government, 2020). These committees are both meant to convene senior officials from over a dozen departments, bimonthly, to discuss cross-cutting issues relating to the government’s approach to climate change.

The Prime Minister chairs the Climate Action Strategy Committee, which is mandated “to consider matters relating to the delivery of the U.K.’s domestic and international climate strategy” (Cabinet Office 2020). The Climate Action Strategy Committee has six departmental members: the Chancellor of the Exchequer; the Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Affairs; the Minister for the Cabinet Office; the Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy; the Secretary of State for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs; and the Minister of State for Pacific and the Environment.

The Climate Action Implementation Committee, meanwhile, considers “matters relating to the delivery of COP26, net zero and building the U.K.’s resilience to climate impacts” and is chaired by the Minister for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy. Membership includes all the Climate Action Strategy Committee members (except for the Minister for the Cabinet Office) as well as the Secretary of State for International Trade, and the President of the Board of Trade; Secretary of State for Work and Pensions; Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government; Secretary of State for Transport; and the Secretary of State for Scotland (Cabinet Office 2020). In this committee, there is concern regarding whether the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy “has sufficient influence to ensure other parts of government take enough action in their areas of responsibility,” as one anonymous source from within government stated in 2021 (National Audit Office 2021). However, both committees provide a forum for high-level leadership to coordinate. The Prime Minister can also provide support to the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy in ensuring cross-departmental climate action via chairing the Climate Action Strategy Committee.

3.2.2. Supporting groups

Two other groups support the cabinet committees: the Climate Change National Strategy Implementation Group, and the Net Zero Steering Board, as seen in Figure 1 below. A director-general from the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy chairs the National Strategy Implementation Group. This Group is comprised of senior officials from the main departments across government and is responsible for implementing a cross-government climate action strategy and covering both domestic and international aspects of mitigation and resilience (National Audit Office 2020). The Net Zero Steering Board supports the National Strategy Implementation Group regarding a net zero strategy specifically (National Audit Office 2020). Both groups report to the two cabinet committees.

3.2.3. Inter-ministerial groups

Besides cabinet committees and advisory groups, two Inter-Ministerial Groups were established in 2018 to focus on issues relating to climate and net-zero policy. The Inter-Ministerial Group for Environment and Clean Growth brings together ministers and officials from across government. The Inter-Ministerial Group for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change helps coordinate between the devolved administrations (Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) on climate change (Inter-ministerial Group for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change 2021). 1 Unlike cabinet committees, inter-ministerial groups rarely have the ability to make any binding decisions but can support policy development in areas where Cabinet consensus is not required. These groups can provide a regular forum for the devolved administrations to communicate and share information on climate policy with a variety of departments, whereas cabinet committees do not tend to have this representation.

In the United Kingdom, cabinet committees can make some binding decisions on specific policy issues to reduce the burden on Cabinet as a whole. Other types of groups, like sub-committees, implementation task forces, or informal groups, do not have this decision-making capability. The precedent in the United Kingdom is to keep details of committee meetings private, so their true impact on policy is difficult to measure (Institute for Government 2020). Complete transparency from these committees is extremely unlikely and may be unnecessary in the presence of other accountability mechanisms. The external Climate Change Committee provides a forum for public debate and analysis, and the Climate Change Act and Net Zero Strategy provide goals by which to measure departmental performance. However, there is a need for more clarity on what these cabinet committees actually do, and the inter-departmental activities they foster.

3.3. Whole-of-government processes

The above structures are tangible mechanisms with clear placements in the government hierarchy—but the United Kingdom has had less success with embedding a whole-of-government approach for climate change into its broader policy processes. At a high level, the 2008 Climate Change Act sets short- and long-term targets for climate action, culminating in net zero by 2050 (as amended in 2019). These targets are one instrument that dictates climate action in each single department, although enforcement of these targets within departments is lacking.

Policies like the 2017 Clean Growth Strategy (under the auspices of the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy) included some whole-of-government processes, although there were persistent gaps between ambition and policy pathways. For example, the Clean Growth Strategy set targets for specific sectors and their respective departments (e.g., a goal of 19 per cent reduction in agricultural emissions, managed by the Department of Agriculture), and referenced the Inter-Ministerial Group on Clean Growth to coordinate between departments (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy 2019). However, in its 2019 progress report to Parliament, the Climate Change Committee stated that a significant gap between policy ambition and climate goals remained, and that many targets were not on track (Climate Change Committee 2019; 2021). These failures are not solely due to an inefficient whole-of-government approach, but nor is this approach the cure-all for missed climate targets in the United Kingdom. It does call into question the efficacy of the current whole-of-government approach.

The United Kingdom has made some progress on whole-of-government procedures since 2019. Following advice from the Climate Change Committee, in 2020 the Johnson government directed the Treasury to undertake a broad review of options for financing the net zero transition, indicating a broader prioritization of climate change across (and beyond) government (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy 2019). In response, the Treasury released an interim Net Zero strategy in December 2020 (HM Treasury 2020). However, critics point to significant existing gaps between Treasury plans and Climate Change Committee goals (Serin 2021).

The Net Zero Strategy, released in October 2021 just days before COP 26, has the potential to galvanize a more coherent whole-of-government strategy. The Strategy indicates a commitment to “further embed climate change in spending decisions,” and “to require the government to reflect environmental issues such as climate change in national policy-making” (Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 2021). The Strategy is relatively comprehensive, informed by the Climate Change Committee’s recommendations, and sets sector-specific pathways with an overall goal of net zero by 2050. However, the projected impacts of specific policies are vague as the government has not quantified the impacts of each policy proposal, and some funding schemes (for buildings and agriculture, in particular) are still in development (Climate Change Committee 2021).

3.4. External advisory bodies

The Climate Change Committee is the United Kingdom’s independent non-departmental public body that advises the government and devolved administrations on climate change. Their public reports and advice to government are crucial in setting long-term climate goals, measuring progress, and developing policy (Cabinet Office 2020). The Climate Change Committee provided several recommendations for the recent Net Zero Strategy, released in October 2021. As discussed above, the whole-of-government approach in the United Kingdom suffers from a lack of accountability and clarity over what these structures and procedures accomplish, and the extent of their capacity to affect change. The Climate Change Committee helps provide some of this accountability by tracking the progress of specific sectors and government action plans, identifying gaps in ambition, and advising the government on ways to close those gaps. The Climate Change Committee provides regular reports to Parliament and advice on specific issues upon Ministerial request, although its operations are wholly independent (Climate Change Committee 2021).

3.5. Key findings

The approach of relying on cabinet-level committees to fulfill a coordinating role for climate change has both best practices to learn from, and pitfalls to avoid. The United Kingdom has established several whole-of-government structures and processes since 2019, notably the Climate Action Strategy and Climate Action Implementation committees. But the country is behind on its climate targets and there is a need for more coherent, cross-government strategy (Climate Change Committee 2021; National Audit Office 2020). Given cross-party consensus on climate change in the United Kingdom, dedicated climate committees will likely endure, ensuring that climate change stays front and centre in government operations.

There is high-level commitment from leaders to climate action between and within departments.Cabinet committees and working groups, established by the Prime Minister and relevant department heads, encourage inter-departmental collaboration on climate change. The cabinet committees in particular provide a tangible forum for departments to coordinate on policy, share information, and discuss climate strategy informally.

However, a change in government could wipe the slate clean of the whole-of-government approach, making these structures and processes fragile. Reliance on Cabinet leadership to advance policy issues is a long-standing issue in the United Kingdom due to a lack of inter-departmental coordination (which this whole-of-government approach aims to mitigate) and frequent turnover of leaders. The nature of the whole-of-government approach depends on central leadership; this dependence can lead to strong inter-departmental coordination if backed by the Prime Minister but is also a fundamental weakness of the United Kingdom approach.

The effectiveness of cabinet committees and working groups depends on the capacity and resources assigned to them by executive leadership, and on the ability to create new policies and plans between departments. However, these committees signal senior political buy-in and committed leadership, which could lead to more concrete action from these structures in the future.

A lack of transparency and accountability mechanisms make it difficult to assess the efficacy of the United Kingdom whole-of-government approach to climate change, and the extent of inter-departmental collaboration and concrete policy change resulting from this approach is unclear. Cabinet committees and working groups rarely release detailed reports, and so the outcomes of these structures are difficult to assess. We need more accountability from these committees to identify the outcomes of these meetings and whether this form of whole-of-government structure actually increases climate action across and within departments.

Case summary

- The United Kingdom has established several whole-of-government structures and processes since 2019, notably the Climate Action Strategy and Climate Action Implementation committees.

- These structures and processes indicate a high-level commitment to climate action between and within departments and encourage inter-departmental collaboration on climate change.

- However, a lack of capacity, transparency, and accountability mechanisms make it difficult to assess the efficacy of the United Kingdom whole-of-government approach to climate change, and the extent of inter-departmental collaboration and concrete policy change resulting from this approach is unclear.

4. Case study: British Columbia

4.1. Context

Following the 2007 Speech of the Throne that stressed the urgency of climate change and British Columbia’s responsibility to act, the province positioned itself as a climate leader in North America and the world. This manifested itself in an ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction target of 33 per cent by 2020 and 80 per cent by 2050 below 2007 levels, and the implementation of a host of policies to deliver on these targets, which included the first carbon pricing policy in a North American jurisdiction—a revenue-neutral carbon tax (Government of British Columbia 2008). Such ambitious legislation came about as a result of a personal learning experience from then-Premier Gordon Campbell, who had engaged personally on the issue and worked with influential figures such as then-Governor of California and outspoken climate spearhead Arnold Schwarzenegger (Harrison 2012).

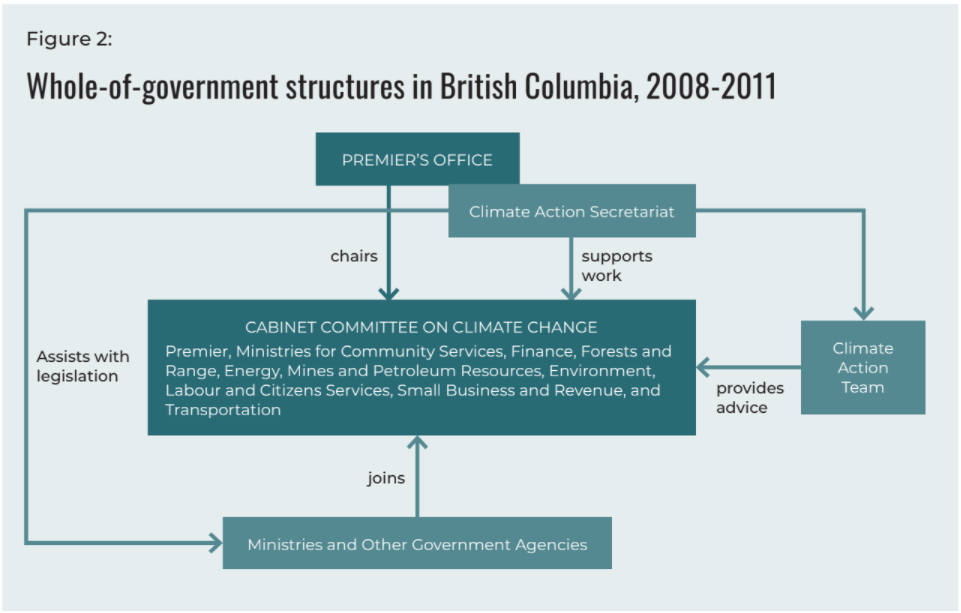

The Campbell government adopted a whole-of-government approach to coordinate the various departments whose sectors are responsible for and affected by climate change. The government created a Cabinet Committee on Climate Action and established a Climate Action Secretariat to manage the cross-governmental approach. In addition, an external advisory body that consisted of representatives from civil society—the Climate Action Team—was also established to provide recommendations on short-term greenhouse gas reduction targets for 2012 and 2016. Since then, the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action and Clean Energy, a Cabinet Working Group on Climate Leadership, a Planning and Priorities Secretariat, and the Climate Solutions Council (a new advisory body) are other examples how the B.C. government further enshrines the whole-of-government approach in climate change policymaking.

4.2. Whole-of-government structures

Several whole-of-government structures dedicated to climate change have been established in British Columbia since 2007 when the issue was a top priority for the government, but there have been important changes in line with changes in government.

4.2.1. Government Secretariats

The Climate Action Secretariat was first established in 2007 within the Premier’s own office and was therefore centrally located in British Columbia’s Executive Council, which provided it with significant weight. This Secretariat was tasked with coordinating climate change across the government and working with almost every ministry, and was accountable to a new Cabinet Committee on Climate Action (Government of British Columbia, n.d.). Moreover, it was also set up to engage with First Nations, local governments, industries, environmental organizations, and the scientific community, support the Climate Action Team, and report on progress. Information on the Climate Action Secretariat and its work was publicly available on a separate subpage of the government’s website.

From 2008 onwards, the Climate Action Secretariat was resourced by the Ministry of Environment but remained located inside the Premier’s Office and accountable to the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action, before it was completely removed from the Premier’s Office after a change in leadership in 2011, when Premier Christy Clark assumed office. While the Secretariat remained in place following this change, its work eventually became less prominent and influential, with fewer updates and less information provided in the Ministry of Environment’s annual reports—it was not mentioned at all in the 2015/16 and 2016/17 editions—and the separate webpage was also taken down and could not be accessed any longer. This resulted from shifting priorities following the outbreak of the 2008 financial crisis and the change of provincial leadership (Lee 2017). It also came at a time when issues like carbon pricing were de-prioritized at the national level in Canada as the federal government of the day preferred regulation as opposed to pricing approaches like the one British Columbia had previously championed, leaving B.C. isolated. Today there is not even an archive of the Secretariat website available publicly, and information on its past work is difficult to obtain.

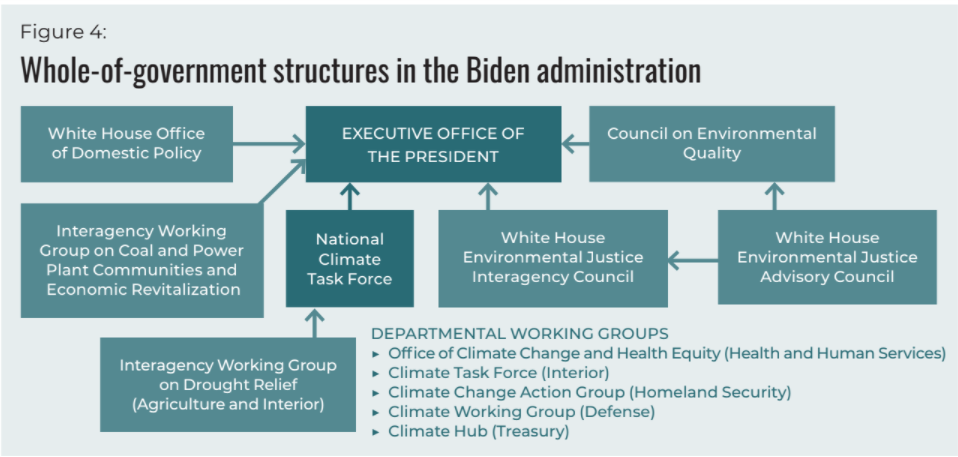

However, the relevance of the Climate Action Secretariat increased again after a change in government in mid-2017, which led to the development of the CleanBC strategy, British Columbia’s next ambitious set of climate change policies. While a greater leadership and coordination role had been hampered because of the Secretariat’s limited human resource capacity, the number of staff seems to have slowly increased over the last few years (Government of British Columbia n.d.; Klein 2020).

After the 2020 election, the government also established a new secretariat within the Premier’s office—the Planning and Priorities Secretariat—to ensure that the scope, direction, sequencing, and delivery of key policy initiatives are aligned with the intentions and priorities of the Premier and Cabinet. This secretariat has been staffed throughout 2021 and will work with ministry executives to define timelines and deliverables for these key commitments and to support effective cross-government responses to emerging high-priority issues such as climate change.

4.2.2. Cabinet committees and working groups

The Cabinet Committee on Climate Action was established in 2007 and came together every two weeks. It was chaired by the Premier himself and brought together the Ministries for Community Services, Finance, Forests & Range, Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, Environment, Labour and Citizens’ Services, Small Business and Revenue, and Transportation to make policy related to greenhouse gas reduction and climate change adaptation (Government of British Columbia 2008). The Committee was established by amending regulations from 2005, and its job was not only reviewing policy options on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also hearing suggestions from key civil society groups (Government of British Columbia 2007). To support this directive, the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action and the Climate Action Secretariat engaged with over 450 groups, individuals, and businesses between May 2007 and June 2008 (Government of British Columbia 2008).

Following the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action, a Cabinet Committee on Climate Action and Clean Energy was in place from October 2009, as well as a Cabinet Working Group on Climate Leadership from January 2016 until mid-2017, when they were both repealed by the new government (Government of British Columbia 2007). It remains unclear which ministries were involved in these committees, how often they met, and what outcomes they achieved.

4.3. Whole-of-government processes

Regarding processes, a whole-of-government approach in B.C. was mostly reflected in the two climate change mitigation plans the government implemented. According to the 2008 Climate Action Plan, “the government is taking focused action to support reductions in each of the Province’s major economic sectors” (Government of British Columbia 2008, 25). Notably, this approach included ministries responsible for transportation, buildings, waste, agriculture, industry, energy, and forestry—which are all emissions-intensive sectors. According to the 2008/09 Annual Service Plan Report of the Ministry of Environment (2009), the “initiatives included in the plan are a result of policy development within the Climate Action Secretariat and ministries, as guided by the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action.” Moreover, the report highlights that the Climate Action Secretariat assisted the ministries in developing policy, legislation, and regulations as required.

Similarly, CleanBC, the climate mitigation plan published in December 2018, also provides a holistic view of addressing climate mitigation by focusing on the various sectors where emissions occur, emphasized also by forewords from the Premier, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, the Minister of Energy, Mines, and Petroleum Resources, and Minister of Jobs, Trade, and Technology (Government of British Columbia 2018). The role of the Climate Action Secretariat was once again instrumental in developing and implementing this plan: the 2019/20 Annual Report of the Ministry of Environment praised the Climate Action Secretariat for “coordinating dozens of new policies and programs across multiple ministries” (B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy 2020).

In addition, the amended Climate Change Accountability Act required the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy to establish sectoral emission reduction targets and report on progress and future proposed actions annually (Government of British Columbia 2019). In March 2021, sectoral 2030 emission targets below 2007 levels were set for transportation (27 to 32 per cent), industry (38 to 43 per cent), oil and gas (33 to 38 per cent), and buildings and communities (59 to 64 per cent), further strengthening B.C.’s whole-of government approach to climate change (Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy 2021).

Finally, the advisory bodies appointed by B.C. governments (discussed below) to provide guidance and recommendations for further climate action also followed a whole-of-government approach when they gave advice. The report of the Climate Action Team in 2008 included specific recommendations regarding the transport, buildings, energy, industry, agricultural, waste, and forest sectors (Climate Action Team 2008); the recommendations from a similar Climate Leadership Team also addressed all these sectors (Pembina Institute 2015); and the Climate Solutions Council advised on various specific topics, such as a strengthened zero-emissions vehicle target, the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, and support for British Columbia’s Emissions-Intensive Trade-Exposed (EITE) industries.

4.4. External advisory bodies

A Climate Action Team comprised of 21 leaders from environmental organizations, private enterprise, the scientific community, First Nations, and academia was formed in November 2007 (Government of British Columbia 2008). Its mandate was to offer expert advice to the Cabinet Committee on Climate Action on identifying interim targets for 2012 and 2016 to complement the 2020 emission reduction target of 33 per cent; identify further actions to meet the 2020 target; and advise on the provincial government’s commitment to become carbon neutral by 2010. It met monthly until the summer of 2008 when it was set to release its recommendations. While the greenhouse gas reduction targets became legislated, many other recommendations became lost in the “bureaucratic shuffle after the Climate Action Secretariat […] was moved out of the premier’s office and into the Ministry of the Environment” (Devine n.d.), according to a former member of this advisory group.

In 2018, the Climate Change Accountability Act legislated a new advisory committee called the Climate Solutions Council that consists of members from First Nations, environmental organizations, industry, academia, youth, labour, and local government to provide strategic advice to government on climate action and clean economic growth (Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy n.d.). This external advisory body provided advice four times in 2020 and, so far, nine times in 2021, including on ways the government can strengthen a whole-of-government approach to climate action through improved communication, coordination, and ambition, such as a whole-of-government “buy clean” policy (Climate Solutions Council 2021). As part of this advice, the council also called the establishment of the Planning & Priorities Secretariat an “excellent first step in ensuring decisions coming to Cabinet committees consider their effects on B.C. climate policy.”

4.5. Key findings

The British Columbia experience is a case study of the highs and lows of a whole-of-government approach to climate action. Launched with much fanfare and a high degree of transparency, at its height it represented a world-leading approach. However, it also became an example of the fragility of these approaches when changes in priorities and leadership of government led to its diminished role and eventually a disappearance from the public eye. That it is difficult today to even find a public record of its past activities speaks to the risks of these approaches if the executive branch of government, which is so critical to their success, no longer carries the motivation and commitment to transparency needed to be successful in the long term. British Columbia’s whole-of-government approach to climate action provides important lessons for jurisdictions that consider a similar approach.

The Climate Action Secretariat was an effective, well-placed whole-of-government structure when organized under the Premier’s Office. At that time, it could benefit from the leverage of the most powerful figure of the Executive Council, which emphasized that climate change was a top priority for the administration and helped it adopt ambitious targets and policies. In contrast, the influence of the Secretariat decreased after it was moved to the Ministry of Environment and lost this prominent (and very public) position.

Lack of sufficient resources was another factor that negatively impacted the results achieved by the Climate Action Secretariat. With more resources, a longer timeframe with these resources, and political support, the experience under the new government from 2017 onwards, when the Climate Action Secretariat regained some of its earlier prominence, shows that it would have been possible to sustain its momentum. With that said, in its heyday around 2008 as well as since mid-2017, the Climate Action Secretariat and the Cabinet Committee have proved relevant and successful, although progress was fleeting in between.

Case summary

- British Columbia’s whole-of-government approach has ebbed and flowed with changes in leadership.

- In particular, the Climate Action Secretariat was an effective, well-placed whole-of-government structure under Premier Gordon Campbell, who established and championed the Secretariat. However, its influence lapsed under successive governments, and transparency remains an issue.

- Processes like the CleanBC plan, implemented in 2018, are an attempt to embed climate change in decision-making processes across government.

5. Case study: The United States

5.1. Context

The United States has attempted to use a whole-of-government approach to address a variety of issues historically, especially regarding national security and intelligence (Brook 2012). Attention to collaborative public sector reform and whole-of-government initiatives lagged slightly behind early pioneers in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, but has increased in the 21st century. The Biden administration committed to a sweeping whole-of-government approach to climate change early, and also pledged to integrate COVID-19 economic recovery plans with climate goals (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a).

Executive leadership (i.e., the President) establishes and controls whole-of-government structures, since use of executive orders to achieve Presidential policy goals is much quicker and more efficient than going through the Congress given the gridlock that has become the norm over the past decade. Because of the deeply partisan character of climate change in the United States, few new climate governance mechanisms have been established in the last two decades, although new responsibilities have been passed onto existing institutions, usually at the executive level (Mildenberger 2021; Dubash 2021). The drawback of this is, of course, that executive orders are easily undone by subsequent Presidents.

The United States tends to make use of Secretary-level task forces for whole-of-government structures. Like Cabinet committees in the United Kingdom and British Columbia, there is a wide spectrum of responsibilities, authority, and capacity to address issues in these task forces. The Biden administration is the first to establish an explicit whole-of-government approach related specifically to climate change.

5.2. Whole-of-government structures

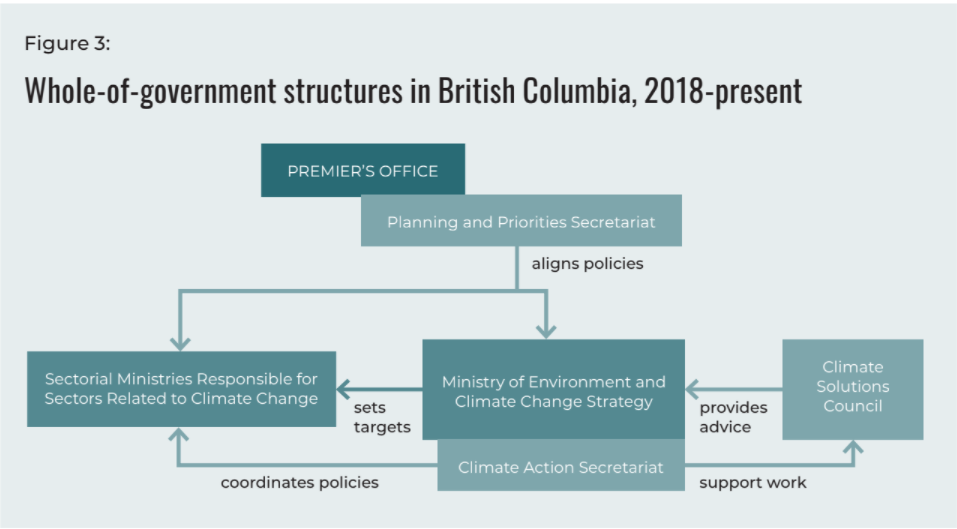

President Biden moved quickly to implement his whole-of-government approach to climate change. Just days after he took office, the Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad was issued. This executive order established a National Climate Task Force and appointed two climate czars: National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy (who previously served as the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under Barack Obama) and Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Change John Kerry.

5.2.1. National Climate Task Force and White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy

The National Climate Task Force “assembl[es] leaders from across 21 federal agencies and departments to enable a whole-of-government approach to combatting the climate crisis” and is chaired by McCarthy. The Task Force focuses on ensuring that each agency integrates climate change into their policy-making processes, with an initial focus on government procurement, sustainable infrastructure investment, clean energy investment, and community revitalization (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a).

Also included in this January 2021 executive order is the establishment of a White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, also led by McCarthy (although with a team of White House aides as members, not departmental representatives), that is “charged with coordinating and implementing the President’s domestic climate agenda” (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a). The Obama administration established a similarly named body—the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy—in 2008, but Congress defunded the office in 2011 after failing to pass a broad climate bill, when priorities shifted towards health care.

Unlike the United Kingdom, which uses existing departments and personnel, Biden has created two new climate-focused offices. Gina McCarthy leads and coordinates the American whole-of-government approach, and so the success of the Task Force and the White House Office relies heavily on her leadership. Thus far, the Task Force seems to be actively encouraging inter-departmental coordination and policy collaboration. McCarthy has directed the establishment of several bilateral interagency structures and processes, like a Working Group to address drought issues with the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior, and increased cooperation between the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Transportation on fuel efficiency standards (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021c). Additionally, the Biden administration is mitigating some of the transparency issues identified in British Columbia and the United Kingdom by releasing a new climate change informational website, meant to showcase the progress of its whole-of-government approach and the actions of the Task Force.

5.2.2. Smaller working groups

In response to Biden’s January 2021 Executive Order, several departments have established their own climate working groups or task forces (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a). The Departments of Health and Human Services, Interior, Homeland Security, Defense, and Treasury have all established climate action working groups or task forces. These groups signal a commitment to climate action across government from Biden and from the Department Secretaries he has appointed.

Biden has also established or re-organized several smaller, issue-specific whole-of-government structures (as seen in Figure 4) like the Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization, 2 the White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council, 3and the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council4 (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a). The two groups on environmental justice often collaborate, but each operates independently. All groups convene with the mandate to increase whole-of-government attention to specific issues (which include but are not limited to aspects of climate action).

5.3. Whole-of-government processes

There are signs of procedural changes that direct increased climate ambition within individual departments as well. Biden’s Executive Order on Tackling Climate Change at Home and Abroad explicitly called for “bold, progressive action that combines the full capacity of the Federal Government with efforts from every corner of our Nation, every level of government, and every sector of our economy” (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a).). Departments are responding to this directive; for example, incumbent Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin released a memorandum showing his support of the directive and outlined steps for his department to take to integrate climate change at all levels (Austin 2021).

Biden has embedded climate change into his American Jobs Plan for economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, job creation, and infrastructure investment, although parts of this proposal face a steep uphill battle in Congress (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021b). Biden’s January 2021 executive order also supports the American Jobs Plan by directing all federal agencies to purchase carbon pollution-free electricity and zero-emission vehicles going forward, and to stimulate clean energy industries (United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden] 2021a). The American Jobs Plan is a good example of a whole-of-government initiative that embeds climate change into an economic policy that affects the activities of almost every agency in the American national government. Questions remain about the outcomes of this policy, if it passes—for instance, it’s not clear how or when agencies will have to incorporate climate action in their reporting—but it is a clear and strong signal from the White House that climate action is a problem for all agencies to solve together.

5.4. Key findings

Biden’s whole-of-government structures are still in their infancy, so it is difficult to ascertain the extent of their authority to make cross-departmental change. However, Biden has shown considerable commitment to climate action within the whole-of-government method compared to both Trump and Obama.

In 2021, the United States has demonstrated committed leadership and has delegated sufficient authority to its whole-of-government structures. The creation of new structures and the appointment of key personnel like Gina McCarthy indicates cross-departmental prioritization of climate change, as does Biden’s record of integrating climate action into COVID-19 recovery efforts.

The National Climate Task Force is the foundational structure of this approach, and thus far results are promising, with issue-specific initiatives coming out of regular meetings. Smaller groups allow for certain sub-groups to work together on specific issues or sectors, while still operating under the broader umbrella of the Task Force.

However, this approach is fragile and may not survive a change in government or a re-allocation of resources. Biden established the Task Force, the White House Office on Climate, advisory positions for both McCarthy and Kerry, and departmental directives to integrate climate action via a few executive orders during his first days in the White House—and these actions are just as easily undone. The ability to quickly establish whole-of-government structures for climate, and give them a fair amount of decision-making capability, is offset by the instability of these structures over time. The National Climate Task Force, likewise, has the potential to make big moves on climate action in the U.S. across departments, but there is still a lot of uncertainty regarding how the Task Force will interact with other agencies and what kinds of policy outcomes will result. Time will tell whether the American whole-of-government approach can serve as a blueprint for climate governance.

Case summary

- The Biden administration has committed to the whole-of-government approach, using executive orders to direct both structural and procedural changes in support of cross-government climate action.

- The National Climate Task Force is the foundational structure of this approach, and thus far results are promising, with smaller cross-departmental initiatives coming out of regular meetings.

- However, this approach is fragile and may not survive a change in government or a re-allocation of resources. Time will tell whether the American whole-of-government approach is best-in-class.

6. Lessons from whole-of-government approaches to climate change

Using a whole-of-government approach, which can encourage inter-departmental coordination and leverage the full expertise of government for ambitious climate action, has appeal for jurisdictions working to achieve climate targets. The whole-of-government approach does not, on its own, equal perfectly implemented climate policy; what it can do is provide central climate leadership that increases accountability and responsibility for all departments (not just environment) and provides a forum for coordination on cross-departmental issues (like building codes or transport standards).

There are several key lessons from these cases that can inform Canada’s governance choices in the future:

- The extent and success of the whole-of-government approach depends on sustained central leadership. In all the cases examined here, executive leaders decided to establish whole-of-government structures (including assigning their membership and areas of responsibility) and create whole-of-government processes. Committed leaders direct the prioritization of climate change in decision-making processes, establish new structures early, and equip them with the resources they need to create new policies and plans across departments.

- The whole-of-government approach is not a silver bullet for good climate governance. Whole-of-government mechanisms are defined by their scope of funding, mandate, and capacity to implement change. Strong legislation can offset some of these issues (like the United Kingdom Climate Change Act), but legislation rarely includes structures like cabinet committees which are established on an ad hoc basis. There is also a question of the ability of these structures to enact change across departments, and to ensure buy-in from a variety of portfolios. Many of these initiatives are at risk of failing because of a lack of direction and resources. As a result, departments that have other priorities and directives have a hard time addressing additional issues meaningfully.

- Installing effective and empowered personnel in whole-of-government structures is essential. Ministers and Department Secretaries or Deputy Ministers have a great deal to do with the buy-in of the whole-of-government approach from single government agencies. If empowered with strong mandates from executive leadership (e.g. in mandate letters), they can leverage this empowerment for action. This is especially apparent in the American case with the post of National Climate Advisor, which directs both the National Task Force and the President’s climate advisory team in the White House Office on Domestic Policy.

- Inter-departmental coordination on climate change must be balanced with allowing departments to fulfill their mandates. Whole-of-government processes can provide direction for prioritizing climate change via mandate letters, department plans, and policies that explicitly require action from multiple departments working together. However, creating too many mechanisms for inter-departmental coordination places an additional burden on departments that already have substantial portfolios. This balance between additional whole-of-government processes and allowing departments to fulfill the rest of their mandate is complicated and difficult to get right. For instance, the United Kingdom case has many of the pieces in place (cabinet-level committees headed by the Prime Minister, directives for each department to address relevant pieces of climate action, broad net zero strategies and external advisory committees to provide policy guidance). However, these pieces have yet to coalesce into an effective whole-of-government approach that truly improves climate governance, largely due to lack of resources, capacity, and vague expectations.

- The whole-of-government approach needs to address accountability, transparency, and reporting requirements in some fashion. Generally, cabinet committees do not release detailed meeting outcomes, which makes it difficult to accurately assess the outcomes of these governance mechanisms. To complicate matters, in some cases, public information is removed with government turnover (as noted in the British Columbia case). Full transparency of these structures is unlikely and implausible, and there are benefits to having closed-door forums for government officials to communicate. However, regular high-level reports that indicate the outcomes of meetings, as well as explicit goals for inter-departmental coordination in mandate letters or delivery plans, would help define the outcomes of this approach. External advisory bodies can provide an important role in increasing the accountability of whole-of-government structures through regular reports on governance approaches and specific advice to government that cuts across departments.

7. Looking ahead for Canada

At the federal level, Canada has already established some whole-of-government structures for environment and climate change, and there are indications that the current government plans to do more. However, Canada could add critical pieces of what would comprise a true whole-of-government approach, such as a cabinet committee, coordinating structures, and clear lines of reporting and accountability.

The Cabinet Committee on Economy and the Environment, chaired by the Associate Minister of Finance, considers climate change as one of several priorities, but there is no cabinet-level committee solely dedicated to climate change. The lack of Prime Ministerial presence in this committee keeps its discussions partitioned, and departmental membership is limited.

Within the Privy Council Office, a small three-person climate secretariat, headed by former Ambassador of Climate Change Jennifer MacIntyre, was established in 2021 to work with the top climate advisors in the Prime Minister’s Office to encourage increased climate action across departments. These postings also indicate a trend of assigning key personnel with strong environmental commitments to multiple key posts, beyond the Ministry for Environment and Climate Change. However, there is room for assigning more ministers and deputy ministers that could play a constructive role in a whole-of-government approach to climate change. Mandating key climate-focused ministers would lead to better uptake within departments and more effective cross-jurisdictional policymaking.

The federal government has proposed a broad integration of climate goals across departments in their 2021 Healthy Environment, Healthy Economy plan, stating that they plan to “apply a climate lens to integrate climate considerations throughout government decision-making.…This transformation will require an aligned approach that ensures that government spending and decisions support Canada’s climate goals” (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2021). More details on how they plan to structure this climate lens will be helpful, as this lens can play a crucial whole-of-government role.

The Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, passed in June 2021, enshrines a net zero commitment by 2050 in law and may prove to be an important whole-of-government process for climate change. For instance, the Act requires the Minister for Finance (in cooperation with the Minister for Environment and Climate Change) to produce annual reports on financial risks related to climate change (Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act 2021). These reporting requirements indicate an opportunity for enhanced inter-departmental collaboration, and for additional expertise to assist non-environment departments in developing climate reports. To this end, the Accountability Act also established the Net-Zero Advisory Body, meant to provide independent advice to the Minister for Environment and Climate Change and other government officials as requested (Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act 2021).

The Advisory Body and the Canadian Climate Institute (established in 2020) serve as external advisory bodies that provide climate policy expertise to government and release independent public research.5 The National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy, established in 1988 and closed in 2012, played a similar role. The Advisory Body and the Institute produce rigorous, transparent, independent research, both to government and the public.

While these plans and legislation signal a commitment to a stronger whole-of-government approach, there is room for more ambition. There are several key pieces that could be added to the Canadian approach, such as a centralized coordinating body and a Cabinet committee.

There are a few ways the Canadian federal government could strengthen its whole-of-government approach:

- A new Cabinet Committee on Climate Change and Net Zero, chaired by the Prime Minister (like the Climate Action Strategy committee in the United Kingdom).

- A high-level coordinating structure to support the Cabinet Committee—a Climate or Net Zero Secretariat—in the Privy Council Office or Prime Minister’s Office, akin to the initial formulation of British Columbia’s Climate Action Secretariat or the United States National Climate Task Force. (The current climate secretariat team in the Privy Council Office would need more financial and human resources to fulfill this role.)

- Under the direction of such a Secretariat, smaller working groups and task forces (like those coming out of the American Task Force) focused on specific issues or sectors. The Secretariat would also develop policy packages for the Cabinet Committee’s approval.

- To mitigate accountability issues, the Secretariat would ideally have a corresponding online repository outlining its progress and plans for whole-of-government work, as the United States has recently released.

Canada is no stranger to inter-departmental coordination or high-level ministerial collaboration, but has not yet designed a truly all-inclusive, cross-jurisdictional approach to climate governance. Taking an effective whole-of-government approach to climate change would go beyond establishing internal committees to instil cross-government climate action across departments, policies, and sectors.

The whole-of-government approach is intended to keep climate action at the centre of all policymaking, leveraging the breadth of public service expertise to mitigate emissions and adapt to impacts more effectively. Inter-departmental collaboration is a foundational aspect of this, since there are multiple departments that need to be involved in solving the cross-jurisdictional aspects of the climate crisis.

The cases presented here identify the need for sustained political leadership, centralized coordination of a whole-of-government approach, clarity of climate goals for departments, and some type of accountability, transparency, and reporting mechanism to assess outcomes. With a well-designed whole-of-government program, Canada can leverage the expertise of its entire public service to raise climate ambition and turn targets into results.

Works Cited

“A Stronger B.C. for Everyone.” BC Budget 2020. https://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/2020 (November 8, 2021).

Australia Management Advisory Committee. 2004. Connecting Government: Whole of Government Responses to Australia’s Priority Challenges. Canberra: Australian Government/Australian Public Service Commission.

Bardou, Magali. 2009. “Public Policies and the Greenhouse Effect.” Ethnologie francaise Vol. 39(4): 667–76.

B.C. Climate Action Team. 2008. Meeting British Columbia’s Targets: A Report from the B.C. Climate Action Team. https://www.bcsea.org/sites/default/files/Climate_Action_Team_Final_Report.pdf (November 8, 2021).

B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy and Environmental Assessment Office. 2019/20 Annual Service Plan Report.

Blair, Tony. 1997. “Bringing Britain Together.” Presented in London. http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=320 (November 8, 2021).

Brook, Douglas A. 2012. “Budgeting for National Security: A Whole of Government Perspective.” Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 24(1): 32–57.

Brook, Douglas A. 2012. “Budgeting for National Security: A Whole of Government Perspective.” Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 24(1): 32–57.

Cabinet Office. 2020. “Written Questions and Answers—Written Questions, Answers and Statements—UK Parliament.” https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2020-02-05/HL1347 (November 8, 2021).

———. “List of Cabinet Committees.” GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-cabinet-committees-system-and-list-of-cabinet-committees (November 8, 2021).

Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act. 2021. (Parliament of Canada) https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-12/royal-assent#ID0ERAA (November 8, 2021).

Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2006. The Whole-of-Government Approach – Regulation, Performance, and Public-Sector Reform. Stein Rokkan Centre for Social Studies. Working paper. https://norceresearch.brage.unit.no/norceresearch-xmlui/handle/1956/1893 (November 8, 2021).

———. 2007. “The Whole-of-Government Approach to Public Sector Reform.” Public Administration Review 67(6): 1059–66.

Climate Change Accountability Act. 2018. (Parliament of British Columbia) https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/07042_01#section4.3 (November 8, 2021).

Climate Change Committee. 2019. Reducing UK Emissions—2019 Progress Report to Parliament. London, U.K.: Climate Change Committee. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/reducing-uk-emissions-2019-progress-report-to-parliament/ (November 8, 2021).

———. 2021a. 2021 Progress Report to Parliament. London, U.K.: Climate Change Committee. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2021-progress-report-to-parliament/ (November 8, 2021).

———. 2021b. Independent Assessment: The UK’s Net Zero Strategy. London, U.K.: Climate Change Committee. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/independent-assessment-the-uks-net-zero-strategy/ (November 8, 2021).

Committees of the Executive Council Regulation. 2009. https://canlii.ca/t/52q6l (October 3, 2021).

CSIRO. 2018. Climate Compass – A Climate Risk Management Framework. CSIRO. https://www.awe.gov.au/science-research/climate-change/adaptation/publications/climate-compass-climate-risk-management-framework.

Dray, Sally. 2021. Climate Change Targets: The Road to Net Zero? House of Lords Library. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/climate-change-targets-the-road-to-net-zero/ (November 8, 2021).

Dubash, Navroz K. 2021. “Varieties of Climate Governance: The Emergence and Functioning of Climate Institutions.” Environmental Politics 30(sup1): 1–25.

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. 2019. Leading on Clean Growth: The Government Response to the Committee on Climate Change’s 2019 Progress Report to Parliament – Reducing UK Emissions. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/committee-on-climate-changes-2019-progress-reports-government-responses.

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Welsh Government, The Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. 2021. Interministerial Group for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change: Terms of Reference. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/interministerial-group-for-net-zero-energy-and-climate-change-terms-of-reference (November 8, 2021).

———. 2021. Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener. London, U.K.: Energy & Industrial Strategy Department for Business. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-strategy.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2021. A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/climate-plan-overview/healthy-environment-healthy-economy.html (November 8, 2021).

Environment and Climate Change Strategy. 2021. “B.C. Sets Sectoral Targets, Supports for Industry and Clean Tech | BC Gov News.” BC Gov News. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2021ENV0022-000561 (November 8, 2021).

Government of British Columbia. 2008. Climate Action Plan. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/climate-change/action/cap/climateaction_plan_web.pdf (November 8, 2021).

———. 2018. CleanBC. Government of British Columbia. https://blog.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/436/2019/02/CleanBC_Full_Report_Updated_Mar2019.pdf (November 8, 2021).

Government of Singapore. 2021. “Singapore Green Plan 2030.” https://www.greenplan.gov.sg/key-focus-areas/overview (November 8, 2021).

Harrison, Kathryn. 2021. The Political Economy of British Columbia’s Carbon Tax. Paris: OECD Working Party on Integrating Environmental and Economic Policies. https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/cote=ENV/EPOC/WPIEEP(2012)16&docLanguage=En (November 8, 2021).

HM Treasury. 2019. HM Treasury’s Review into Funding the Transition to a Net Zero Greenhouse Gas Economy: Terms of Reference. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-review-terms-of-reference/hm-treasurys-review-into-funding-the-transition-to-a-net-zero-greenhouse-gas-economy-terms-of-reference (November 8, 2021).

Horne, Matt et al. 2015. B.C. Climate Leadership Team Process and Recommendations. Pembina Institute. //www.pembina.org/pub/b-c-climate-leadership-team-process-and-recommendations (November 8, 2021).

Institute for Government. 2017. “Cabinet Committees.” The Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/cabinet-committees (November 8, 2021).

Klein, Seth. 2020. A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency. Toronto, Ontario: ECW Press.

Lee, Marc. 2017. “The Rise and Fall of Climate Action in BC.” Policy Note. https://www.policynote.ca/the-rise-and-fall-of-climate-action-in-bc/ (November 8, 2021).

Lloyd Austin. 2021. “Establishment of the Climate Working Group [Memorandum].” https://media.defense.gov/2021/Mar/10/2002597518/-1/-1/0/ESTABLISHMENT-OF-THE-CLIMATE-WORKING-GROUP.PDF (November 8, 2021).

Lockwood, Matthew. 2021. “A Hard Act to Follow? The Evolution and Performance of UK Climate Governance.” Environmental Politics 30(sup1): 26–48.

Meadowcroft, James. 2009. “Climate Change Governance.” Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN Scholarly Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1407959 (August 19, 2021).

Mildenberger, Matto. 2021. “The Development of Climate Institutions in the United States.” Environmental Politics 30(sup1): 71–92.

Ministry of Environment. 2009. 2008/09 Annual Service Plan Report. https://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/Annual_Reports/2008_2009/env/env.pdf (November 8, 2021).

Mulgan, Geoff. 2005. “Joined-Up Government: Past, Present, and Future.” In Joined-Up Government. Oxford: British Academy. https://britishacademy.universitypressscholarship.com/10.5871/bacad/9780197263334.001.0001/upso-9780197263334-chapter-8 (October 27, 2021).

Naomi Devine. “Building on BC’s Climate Action History through Local Government Leadership.” Smart Prosperity Institute. https://institute.smartprosperity.ca/content/guest-blog-building-bc-s-climate-action-history-through-local-government-leadership (October 3, 2021).

National Audit Office. 2020. Achieving Net Zero. London, U.K.: National Audit Office. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/achieving-net-zero/ (November 8, 2021).

National Climate Change Secretariat of Singapore. “Inter-Ministerial Committee On Climate Change.”. https://www.nccs.gov.sg/who-we-are/inter-ministerial-committee-on-climate-change/ (November 8, 2021).

National Archives. 2008. “Records of the Department of Energy and Climate Change: Departmental Websites, and Websites of Associated Agencies and Bodies-—Office of Climate Change”. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C18110

Parliament of Australia. Australian Government Disaster and Climate Resilience Reference Group – Terms of Reference (May 2020)’. Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements. https://naturaldisaster.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/exhibit-5-001023-haf800100010733-annexure-r-australian-government-disaster-and-climate-resilience-reference-group-terms-reference-may-2020 (November 8, 2021).

Prime Minister’s Council for Science and Technology. 2020. Achieving Net Zero Carbon Emissions through a Whole Systems Approach. London, U.K.: Council for Science and Technology. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/achieving-net-zero-carbon-emissions-through-a-whole-systems-approach (November 8, 2021).

Serin, Esin. 2021. “HM Treasury’s Net Zero Review: The Bedrock of a Just Transition?” https://www.businessgreen.com/opinion/4027231/hm-treasury-net-zero-review-bedrock-transition (November 8, 2021).

United States, Executive Office of the President [Joe Biden]. 2021a. Executive Order No. 14008 Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/ (November 8, 2021).

———. 2021b. FACT SHEET: The American Jobs Plan. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/31/fact-sheet-the-american-jobs-plan/ (November 8, 2021).

———. 2021c. Readout of the Third National Climate Task Force Meeting. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/21/readout-of-the-third-national-climate-task-force-meeting/ (November 8, 2021).

Verhoest, Koen, Geert Bouckaert, and B. Guy Peters. 2007. “Janus-Faced Reorganization: Specialization and Coordination in Four OECD Countries in the Period 1980—2005.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 73(3): 325–48.

Footnotes

- It is important to note that while lists and memberships of cabinet committees are published fairly regularly, information on the Inter-Ministerial Groups is rarely released to the public and often must be obtained via a freedom of information request. In 2018, the Institute for Government filed such a request and as such this is the most up-to-date information that is publicly accessible. To illustrate further, while the IMG for Environment and Clean Growth was established in 2018, in 2021 the National Audit Office was unable to clarify if the group had been convened (NAO2021).

- The Interagency Working Group is chaired by the National Climate Advisor and housed within the Department of Energy. Agencies represented include the Treasury, Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, Health & Human Services, Transportation, Energy, Education, the EPA, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Appalachian Regional Commission.

- Formerly within the EPA but now elevated to the Executive Office of the President, the Interagency Council is chaired by the head of the Council on Environmental Quality.

- The Advisory Council is made up of non-government members, is concerned with incorporating environmental and climate justice across government, and is meant to advise the Council on Environmental Quality and the White House.

- Not all of the Net-Zero Advisory Body’s reports will be made fully public. Annual reports and other studies will be public, but specific advice to the Minister for Environment and Climate Change and other officials may be redacted.