This essay was commissioned to inform the research and recommendations in our report Sink or Swim: Transforming Canada’s economy for a global low-carbon future, as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

“A country cannot have a comprehensive economic plan without a comprehensive climate plan,” were the words of Jonathan Wilkinson, Canada’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change, at an April 2021 Canadian Chamber of Commerce Executive Summit. It is here, at the intersection of Canada’s climate and economic planning, where the opportunity lives.

This paper will focus on applying the concept of Indigenomics—a new model of development that advances Indigenous self-determination, collective well-being, and reconciliation—to the economic risks and opportunities that are arising from the global low-carbon transition. I will highlight issues such as Indigenous climate justice, sovereignty, self-determination, and risk management, and explore traditional Indigenous knowledge and data systems and the importance of elevating the role and voice of Indigenous stewardship in a climate action response.

What is Indigenomics?

Indigenomics draws on ancient principles that have supported Indigenous economies for thousands of years and works to implement them as modern business practices.

Indigenomics, as a new word and concept, serves to call into visibility the relevance of an Indigenous worldview in today’s modern economy. Indigenomics is the conscious claim to, and the creation of, space for the advancement of today’s emerging Indigenous economy. Indigenomics is essentially a statement of claim of Indigenous space in modern existence. It is a call-out or invitation into an Indigenous worldview that seeks to centre that worldview in the concepts and experience of “development” and “progress.”

Indigenomics is the conscious claim to, and the creation of, space for the advancement of today’s emerging Indigenous economy

As I explain in my book Indigenomics:

While the Western mainstream economy is geared toward monetary transactions as a source of exchange, the Indigenous economy is based on relationship. Indigenous economies are the original sharing economy, the original green economy, regenerative economy, collaborative economy, circular economy, impact economy, and the original gift economy. The Indigenous economy is the original social economy.

Indigenomics is the process of claiming a seat at the economic table. It involves centring Indigenous rights to an economy, rights to modernity, and rights to be consulted and to provide consent. It is interwoven with the establishment of legal pressure points for economic inclusion, higher standards of stewardship, collaborative decision making, and reciprocal prosperity.

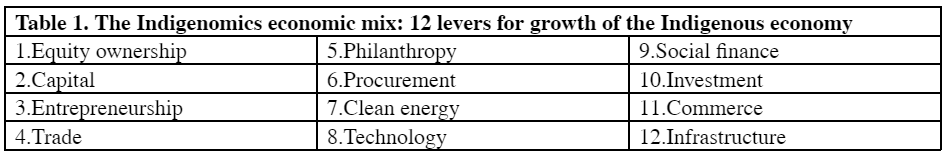

Economic inclusion, reconciliation, and equality do not just happen by themselves. They must be designed. Governments can use a variety of policy tools to support and enable Indigenous efforts to capture economic opportunities, including those that emerge in the transition to a low-carbon economy (Table 1).

The connection between Indigenous rights and knowledge and climate change

The concept of environmental justice refers to the impacts of both historical and current inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental degradation, including the consequences of climate change. This includes the experiences of Indigenous Peoples bearing a significantly greater portion of the costs, while receiving relatively little in return.

Indigenous Peoples live the long-term cumulative effects of climate change from within an inherent sense of place that is directly connected to identity. Some of these effects include rising sea levels, leading to increased salination of freshwater, which results in needing to adapt to the effects of a significant decrease in food security and access to traditional medicines, amongst other impacts. Indigenous knowledge systems offer a critical foundation for localized, community-based adaptation and mitigation actions that work to fundamentally sustain the resilience of social-ecological systems locally, regionally, and globally.

There is a growing recognition that Indigenous Peoples’ rights and knowledge systems are critical to developing solutions to the climate crisis and achieving climate justice. Indigenous Peoples have a crucial role in this national and global response. Indigenous Peoples are on the front line of the effects, and stewards of critical ecosystems that store vast amounts of carbon. With memories of place going back thousands of years, subtle changes to the lands and waters are noticed immediately. Indigenous Peoples have been the eyes on the land for thousands of years and will continue to be in the future.

Indigenous concepts of risk, land and resource management, governance, and decision making were systematically devalued in the development of what we call Canada today. This systematic economic displacement also displaced Indigenous ways of being, knowledge systems deeply connected to land, and resource management frameworks expressed within a way of life. Indigenous cultures had, and continue to have, the key features for long-term success and relationship with our environments.

As enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the principles of upholding free, prior, and informed consent and self-determination are pillars of climate justice and central to building a response to climate change. UNDRIP recognizes the right to continue as distinct peoples and to practice our culture, which becomes increasingly difficult in rapidly changing ecosystems impacted by climate change.

The process of colonization established the reserve system, which fundamentally isolated Indigenous Peoples from their territories and created economic isolation and displacement. The Indian Act removed Indigenous inherent sense of responsibility for place, replacing it with externally imposed structures and deepening the marginalization of Indigenous Peoples.

Indigenous Peoples cannot remain on the margins of the transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy. Subtle changes in seasonal patterns and other imbalances are noticed. In the words of Indigenous climate leader Eriel Deranger of Indigenous Climate Action, “It is a close relationship with the environment, and deeply spiritual, cultural, social, and economic connections with that environment, that makes Indigenous peoples uniquely positioned to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to the impacts of climate change.” She emphasizes that Indigenous science is rooted in profound and lasting connections with the natural world: “You learn to have a different relationship with the environment, it exposes to you a different way of seeing and relating to the world.”

Indigenous climate leadership

There are so many great examples of Indigenous climate leadership laying the groundwork for a response to climate change rooted in Indigenomics. Here are six initiatives that demonstrate Indigenous climate leadership on the front lines of environmental justice:

- Indigenous Climate Action is demonstrating real-time leadership in the establishment of an Advisory Council on Decolonizing Climate Policy. Some may wonder, what does it mean to decolonize climate policy? It is effectively a response to the overreach of, and blind spots within, existing climate policy. The failure to include Indigenous voices within emerging climate policy has left out important perspectives and led to incomplete and inequitable policies. As a recent article titled “How Are Vulnerable Populations Impacted by Carbon Pricing Schemes in Canada?” points out, Canada’s extensive focus on developing provincial pricing schemes and benchmarks has neglected to consider how these policies will impact vulnerable populations and Indigenous communities in Canada.

- Coastal First Nations, a unique alliance of nine B.C. First Nations, is establishing structures that align the development of Indigenous-led sustainable economies through marine, land, and resource regional planning in order to increase local control and management of the forests and fisheries. By establishing ecosystem-based management plans and legal frameworks, and by empowering Indigenous Guardians to act as stewards of the land, the Coastal First Nations have rooted their governance and resource management systems in a sustainable development framework capable of responding to the threat of climate change. By pairing scientific data and traditional knowledge, these initiatives provide better insight into adapting to changes.

- Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) are increasingly being established by Indigenous communities. Often referred to as Indigenous Protected Areas, or Tribal Parks, these conservation areas are declared under an Indigenous nation’s own inherent authority. There is a good example of this in my own home territory in the Nuu chah nulth region near Tofino, where the Tla o qui aht Nations Tribal Park has been established. The nation’s mandate for the Tribal Park is to recognize and uphold their people’s ancient relationships and responsibilities within the web of life that exists in this place—and to use their traditional teachings to welcome, balance, and inform newcomers’ influences and impacts. The park includes local Guardians who tend to what is referred to as “our Ancestral Gardens,” which includes the largest intact ancient coastal rainforest on Vancouver Island. With a growing network of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas nationally, these Indigenous-led structures can play a significant role in the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and data development to support a low-carbon regional response.

- The Indigenous Guardians Program is playing a growing role in climate-relevant nature conservation. Through land-based management and knowledge systems, Indigenous Peoples exercise responsibility in the stewardship of traditional lands and waters. This program serves to support Indigenous rights and responsibilities in protecting and conserving ecosystems while developing and maintaining sustainable economies.

- The RELAW program recognizes the shifting interface between law and Indigenous lands. This program draws on the role of traditional stories and the wisdom of elders to help develop a summary of legal principles related to land, resource, and environmental governance in the community’s legal tradition. Part of this includes the development of a written law, policy, agreement, or plan grounded in the community’s own laws and ratified by community dialogue. Finally, the group works to develop and put into action a plan for implementing and enforcing the nation’s laws on a particular environment or resource development issue. Indigenous law is playing an increasingly important role in driving climate solutions, policies, and responses at a local level.

- The Great Bear Forest Carbon Project is led by nine coastal First Nations. It makes up the world’s largest forest carbon initiative, selling annual offsets from protected forest areas that were previously designated, sanctioned, or approved for commercial logging. Considerable amounts of carbon are stored within the extensive area of old growth forest within the Great Bear Rainforest located on the North and Central Pacific Coast and Haida Gwaii. This forest represents over one quarter of the world’s remaining coastal temperate rainforests. Indigenous leadership has driven the development of this carbon project. The Indigenous Peoples of this region have lived in this location for over 14,000 years, and their land use laws and practices are rooted in the understanding that keeping the ocean and forest ecosystems healthy is the key to our collective success. Indigenous-led carbon initiatives are an essential pathway forward.

Integrating Indigenomics into economic and climate plans

To the words of Minister Wilkinson—“A country cannot have a comprehensive economic plan without a comprehensive climate plan”—I would add: or without Indigenous knowledge systems.

The Indigenous economy exists within our relationship to ourselves, to each other, to the Earth, to our past, and to our future. The concept of interconnectedness within the Indigenous worldview pushes the boundaries of time within community development and decision making. The underlying principles of emerging economic constructs such as the green economy parallel Indigenous values and ways of being—at the core of which is the commitment to remember how to be in relation to each other and to the Earth.

It is not possible to develop a green economy or low-carbon transition strategy without recognizing the need for economic reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. The core of economic reconciliation is supporting Indigenous communities so that they have access to the capital, resources, and opportunities needed to succeed. This includes capturing growing opportunities in clean energy and other economic development opportunities linked to climate action.

It is time to integrate Indigenomics into both economic and climate plans.

Carol Anne Hilton is founder of the Indigenomics Institute and an advisor to business, governments, and First Nations. She is a Hesquiaht woman of Nuu chah nulth descent from the west coast of Vancouver Island. She holds an MBA and comes from 10,000 years of the potlatch tradition. She lives in Victoria, BC.