In particular, shared jurisdiction between provincial, territorial, federal, municipal, and Indigenous governments in developing and implementing climate change policy introduces complexity to designing a climate accountability framework for Canada. Notably, a Canadian climate accountability framework will also need to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ inherent rights, as affirmed by Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution, and reflect the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, to which Canada is a signatory.

In this section, we discuss Canada’s challenges and opportunities and present three design choices central to determining how climate accountability could work in the Canadian federal context.

Canada’s unique challenges and opportunities

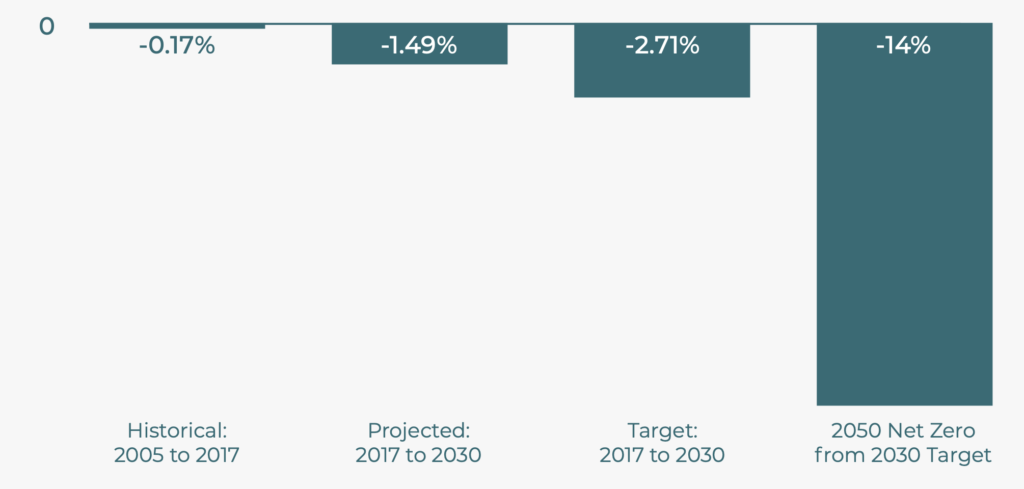

Several factors define the Canadian context. First, aligning Canada’s emissions trajectory with the federal government’s net zero target will require policy ambition and stringency well beyond anything seen to date. Figure 1 illustrates the magnitude of the challenge. Between 2005 and 2017, Canada’s GHG emissions declined about 0.2 per cent per year, falling from 730 to 715 million tonnes. Looking forward to 2030, Environment and Climate Change Canada projects GHG emissions will decline by 1.5 per cent per year. This greater projected rate of decline reflects the recent rise in climate policy ambition by Canadian governments. However, to achieve Canada’s 2030 target of 511 million tonnes, the projected 1.5 per cent annual decline will need to nearly double to 2.7 per cent per year to 2030. And to reach net zero by 2050, the annual rate of GHG emissions reductions will, assuming a linear decline rate to net zero, need to average an unprecedented 14 per cent per year after 2030.

Figure 1: 2005 to Net Zero: Average Annual Change in Carbon Emissions1

Importantly, policy-makers need not start from scratch in addressing Canada’s GHG reduction challenge. Rather, they can build on existing policies, processes, and governance structures. Emissions reductions targets and policies are not new concepts in Canada, and neither are climate accountability frameworks. In 2018, Manitoba became the first province to adopt interim emissions reduction milestones through its Climate and Green Plan Implementation Act. Its Carbon Savings Account sets five-year cumulative carbon budgets and is supported by an independent Expert Advisory Council. British Columbia’s climate accountability framework, introduced through its amended Climate Change Accountability Act, established emissions reduction targets, including targets at the sector level, as well as an external advisory body.

Canadian governments also have experience in implementing systems and policies akin to some individual elements of climate accountability frameworks. For example, cap-and-trade systems, like those in Quebec and Nova Scotia, have emissions caps—akin to emissions milestones—that establish the total level of allowable emissions for a given period. And if made binding through regulations, Alberta’s 100 Mt annual cap on oil sands emissions would represent a sectoral cap, while its now- defunct advisory group provides an example of an independent body that can provide input on cap setting.

Nevertheless, building this capacity and experience into a fully scoped Canadian climate accountability framework will pose challenges. A cap-and-trade system, such as the one Quebec has implemented, embodies only one of the numerous features of an accountability framework that we detail in Section 2. And building an accountability framework at the national level will pose unique challenges.

Canada’s decentralized structure of governance and shared jurisdiction

over climate policy will require careful navigation of a sensitive intergovernmental landscape. It will require balancing nationally coordinated climate policy processes with provincial and territorial autonomy, as well as Indigenous right to self-determination. And it will require doing so in a way that recognizes the diversity of Canada, where economies, emissions profiles, and opportunities to reduce emissions differ greatly across regions.

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change reflects the country’s most recent efforts to develop a national climate change plan through a combined federal- provincial approach, resulting in both successes and ongoing challenges. The inter-jurisdictional tensions that have emerged from the implementation of the Pan-Canadian Framework are likely to only intensify (at least in the near term), as reaching milestones consistent with a pathway to net zero will demand steep and ongoing increases in policy ambition. And it will have to occur against a backdrop of significant divergences in climate ambition across different orders of government, where some jurisdictions even question the legality of federal climate policy. The forthcoming Supreme Court of Canada decision on the constitutionality of the federal Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act will help resolve some of this uncertainty and will have important implications for the federal government’s role in climate policy-making in Canada.

A final challenge—and opportunity—is the need for climate accountability frameworks in Canada to recognize, respect, and safeguard Indigenous rights and embed Indigenous expertise, including in decision-making positions, at every stage of the process. Aotearoa/New Zealand’s experience can offer helpful lessons for Canada in this respect (see Box 2). However, Aotearoa/ New Zealand’s approach is unique to its context and cannot simply be replicated in Canada. There are profound differences between the experience of Indigenous Peoples across and within both countries—including historical context, constitutional and treaty rights, culture, language, and diversity—that must be acknowledged. In particular, the Treaty of Waitangi (an agreement signed between the Crown and Māori chiefs in 1840) is widely accepted in Aotearoa/ New Zealand as a constitutional document that establishes and guides the Crown-Māori relationship. However, while the Treaty is well established, Treaty rights are only enforceable in court when a statute or act explicitly refers to the Treaty, as is the case in the Zero Carbon Act.

Box 2: The role of Māori in developing and implementing New Zealand’s Zero Carbon Act

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Government worked closely with iwi and Māori throughout the development of the Zero Carbon Act. The legislation features frequent consultation and engagement with Māori and iwi representatives, consideration of Indigenous knowledge, and recognition of the Treaty of Waitangi. For example, the legislation requires that:

▶ The government’s emissions reduction plans include a strategy to recognize and mitigate the impacts of emissions reduction actions on iwi and Māori as well as ensure that they have been adequately consulted on the plan;

▶ The national adaptation plan takes into account the economic, social, health, environmental, ecological, and cultural impacts of climate change on iwi and Māori;

▶ Particular attention is paid to seeking nominations for the Climate Change Commission from iwi and Māori representative organizations; and

▶ Before recommending the appointment of a member to the Commission, the minister considers the need to have members who have technical and professional skills, experience, and expertise relevant to the Treaty of Waitangi, as well as the Māori world, customs, language, and knowledge.

Although the legislation requires that members of the Commission have understanding and expertise relating to Māori rights and knowledge, the legislation does not explicitly require Māori representation. However, after Māori leaders pressed the government to have a voice at the table, a Māori representative was ultimately appointed as Deputy Chair of the Commission. The Aotearoa/New Zealand Māori Council came out in support of the Zero Carbon Act in advance of its passing in parliament.

Despite the scale of these challenges, establishing a climate accountability framework here could help Canada implement meaningful climate policy and move past its history of uneven implementation, insufficient action, and periodic swings in policy ambition on the part of territorial, provincial, and federal governments. The governance processes under an accountability framework provide a constructive platform for difficult policy debates. They support improved inter-governmental policy coordination. And they empower citizens and stakeholders to better hold governments to account. These features can improve policy certainty and help ensure that the response Canada marshals to its climate change objectives, including its target of net zero emissions by 2050, is cohesive and robust. Moreover, this kind of framework can also help Canada address other long-term policy challenges, such as driving innovation, economic diversification, and inclusive growth.

Key choices in designing and implementing climate accountability frameworks in Canada

Implementing climate accountability frameworks in Canada will require policy-makers to make some difficult choices. While Canadian governments can draw important lessons from the common elements and best practices outlined in Section 2, these case studies offer imperfect lessons for how climate accountability frameworks can be designed to function, and succeed, in the Canadian federation.

In this section, we explore three key choices in designing a climate accountability framework that will have significant implications for the fundamental approach the country adopts, how climate accountability will play out in the federation, and, by extension, how successful it will ultimately prove as a tool to support the attainment of Canada’s targets. The three choices are: 1) where milestones bind; 2) what the process is for setting the milestone pathway; and 3) which orders of government develop policy to meet milestones. For each choice, we present a spectrum of available options and discuss the trade-offs they each present.

Where do milestones bind?

Three broad options for Canada illustrate the range of possibilities for defining the level at which milestones could legally bind under a climate accountability framework.

1. Legally binding milestones are set only at the national level.

Given shared federal and subnational jurisdiction over climate policy, this option could sidestep contentious decisions around how provinces and territories share the burden of addressing climate change. However, it may only defer difficult burden-sharing debates and decisions, since these will inevitably arise when governments are crafting policy for meeting national-level milestones. This option also centralizes responsibility for meeting a national milestone to the federal government, potentially downplaying the role of other orders of government.

2. Milestones are broken out at the provincial and territorial level.

Setting legally binding subnational milestones would allow policy-makers to account for the unique economies, GHG emissions profiles, and emissions reduction opportunities that exist in different regions of the country, while clearly signalling the level of emission-reduction effort required. This approach would also increase policy certainty for consumers, businesses, investors, and other governments by providing more specificity. Notably, despite the fact that this option breaks out milestones at the provincial or territorial level, the federal government would be the accountable entity.2 Further, setting carbon budgets at subnational scales also leads to less flexibility in meeting the overall national budget.3 As a result, it could increase the cost to the economy of achieving a given level of emissions reductions by forcing reductions to take place in particular regions even when more cost-effective actions were available elsewhere. Perhaps most significantly, this option faces the challenge of defining regional burden-sharing head-on. The related question of who sets emissions milestones in the first place (which we discuss below) will therefore be a critical and highly challenging decision.

3. Milestones are broken out at the sector level.

Sector-level milestones would provide more concrete signals for policy-makers, industry, and society relative to the other options in terms of how and where emissions reductions should occur. Sectoral targets have precedent in Canada. At the provincial level, British Columbia’s Climate Change Accountability Amendment Act 2019 commits to setting sectoral targets by 2021, which are to be reviewed every five years. And Alberta’s 100 Mt cap on oil sands emissions is a kind of sectoral carbon budget.4 Despite these strengths and precedents, binding sector-level milestones risk being overly inflexible. Imposing milestones on economic sectors and locking in their emissions reduction trajectory risks creating rigidities that raise the overall cost of mitigation. First, fixed sectoral pathways would not be flexible to changes in the availability and costs of emissions reduction opportunities across sectors due to developments in technology or innovation. Second, the degree to which sectoral milestones bind will in part depend on overall sectoral output, which will itself be affected by broader economic forces. As a result, rigid sectoral targets would not be adaptive to shifting emissions reduction opportunities and costs across sectors and would risk forcing costly reductions in some parts of the economy while more cost-effective ones are available elsewhere. Achieving sector- level milestones may also require sector-specific policy levers.

What is the process for setting the milestone pathway?

Best practices suggest that a wide range of stakeholders, experts, and orders of government should be involved in the process for setting the milestone pathway. In Canada, an independent expert advisory body should play a central role, as should Indigenous governments and representative organizations. Nevertheless, there is a range of possibilities for how the pathway is set and who is ultimately responsible for setting it. We outline four broad options for establishing processes to define emissions milestones and pathways for Canada.

1. Provinces and territories define their own pathways.

Provincial and territorial governments could independently define subnational milestones (where applicable), the sum of which would define national milestones. Depending on where milestones bind under the accountability framework, these targets would be established for either the subnational jurisdiction as a whole or specific sectors within it. This option presents the greatest opportunity for provincial and territorial buy-in, as it allows subnational governments to set their own targets and ambition. It also enables ambition to be set in a way that reflects the unique economies, emissions profiles, and emissions reduction opportunities of different regions. However, it does nothing to resolve the risk that the sum of provincial and territorial GHG reduction ambition will be insufficient to meet the national long-term target. It also raises important considerations about the role of Indigenous governments in defining their own pathways.

2. Provincial, territorial, Indigenous, and federal governments collectively determine the pathway.

Under this option, multiple orders of government would, with input from the expert advisory body, collectively agree on the milestones and (where applicable) how they will break out into subnational and/or sectoral milestones. They would also engage and consult with key stakeholders (including private-sector representatives and civil society), as well as municipal governments, to inform their decision-making. This kind of inclusive, collaborative approach to milestone setting presents both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, it could result in greater buy-in from different orders of government and establish the groundwork for deeper policy coordination—a significant benefit given that the need for coordination will likely only intensify over time as policy stringency increases. On the other hand, this kind of approach has a high likelihood of creating lengthy, or even deadlocked, negotiations where consensus could be difficult or impossible to achieve.

3. Federal government sets the milestone pathway, based on consultation and engagement.

In this option, the final decision on setting milestones lies with the federal government. Its decision-making would be informed by engagement and consultation with the expert advisory body, other orders of government, key stakeholders including industry and environmental organizations, and Indigenous Peoples. This is a familiar approach, as it follows Canada’s history of directly setting national emissions reduction targets—notably the 2030 target as outlined in the Nationally Determined Contribution—with some degree of consultation. Comprehensive consultation can add a time- and resource- intensive step to milestone setting; however, it also helps enhance buy-in from affected stakeholders and allows important perspectives and circumstances to be raised and considered. While this option makes the process of milestone setting comparatively straightforward relative to the previous two options, policy coordination challenges are likely to be difficult under this approach since subnational governments may not feel ownership over the milestone pathway that emerges (however defined or broken out).

4. Expert advisory body determines the milestone pathway.

Under this option, an independent expert advisory body would be given complete authority to set the milestone pathway, as well as to break it out where applicable. While its decision would still be based on consultation and engagement with governments, Indigenous Peoples, and stakeholders, the expert body would ultimately make the final decision. On the one hand, this option ensures that the milestone pathway is set based on science and expert advice, which enhances credibility by taking real or perceived political influence out of the decision-making process. This approach also avoids lengthy or deadlocked negotiations between governments, which supports timely decision-making. However, this option does not directly support federal or subnational government buy-in or collaboration, and it risks limiting governments’ ownership of the milestone pathway.

Which orders of government develop policy to meet milestones?

Regardless of how milestones and pathway are set, they are only effective if governments implement policies consistent with achieving them. Climate accountability frameworks can define various roles for federal, provincial, and territorial governments with a variety of respective roles in the development of policy to meet defined milestones. We outline three main options:

1. Federal government drives policy.

Under this approach, the federal government uses a set of new or strengthened federal policies to fill the gap left by existing provincial, territorial, Indigenous, municipal, and federal commitments. For example, the federal government could increase the stringency of the federal carbon price or the federal Clean Fuel Standard to close the gap, or it could implement entirely new policies. Making a single government responsible for developing policy to meet milestones could simplify policy development for meeting milestones. On the other hand, it limits the levers available to reduce emissions, since the federal government has different policy instruments, authorities, and powers than provincial and territorial governments. By establishing a smaller, more reactive role for provincial and territorial governments, this option risks reducing their ability to proactively participate in climate policy development and closes off the possibility of customizing policies to reflect unique regional contexts and challenges.

2. Provincial, territorial, and federal governments contribute, with a federal policy backstop.

In this option, federal, provincial, and territorial governments work together on a more equal basis to develop policies in their respective jurisdictions to meet milestones. Under this option, the federal government could encourage provincial and territorial ambition in various ways, including program spending or direct financial transfers. See Box 3 for details. The threat of a federal “backstop” in the case that provincial or territorial policies were insufficient would also create incentives for provinces and territories to implement more stringent policy. A federal policy backstop could include strengthening the federal carbon price or raising energy efficiency standards, among other things. If the federal assessment determined that the provincial or territorial policy were sufficient, the backstop policy would not be implemented. Provinces and territories would have the opportunity to customize policy, where possible.

This approach effectively makes federal, provincial, and territorial governments jointly responsible for implementing policy that contributes to national milestones. It builds on the existing landscape in Canada where policies at these levels of government contribute to reducing GHG emissions. However, collaboration on policy development requires time and resources, and its success will rely on the willingness of all governments to do so in good faith by developing, revising, and likely strengthening their own policies based not only on their own objectives but also those of other governments. This approach also raises unresolved questions about the role of Indigenous governments in climate policy development and implementation.

3. Provincial and territorial governments drive policy.

In this option, provincial and territorial governments develop policies to meet milestones, with the federal government only playing a convening role or supporting provincial policy ambition by using financial incentives. Akin to the bottom-up process under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the federal government could invite provinces to come forth with their own plans, based on their own assessment of what is ambitious and fair. In the Canadian context, in the event of a gap between provincial and territorial contributions and national milestones, the federal government could facilitate a negotiation with provinces and territories aimed at increasing their policy stringency. It could also encourage greater provincial and territorial ambition using its spending powers. Under this approach, provinces and territories would consult with self-governing Indigenous communities on policy choices.

This option could sidestep possible tensions and save the time and resources associated with pursuing more coordinated policy within the federation. It does not, however, ensure that, when taken together, provincial and territorial policies will be sufficiently ambitious to reach national milestones—as has been the challenge until now. As a result, it is not clear that this option can be consistent with a climate accountability framework that includes national, legally binding milestones.

Box 3: Incentives and disincentives for developing policy sufficient to meet milestones

The federal government has a range of tools it can use to encourage provinces and territories to develop policies consistent with national or subnational milestones.

Incentives

Federal spending powers could be used in a number of ways to encourage provinces and territories to implement measures consistent with emissions reduction milestones. For instance, federal programmatic spending could be used to support the emissions reductions priorities of provincial, territorial, Indigenous, and municipal governments: for example, through the Low Carbon Economy Fund under the Pan-Canadian Framework. Spending could support a broader portfolio of climate change objectives, including adaptation and clean growth, or even provincial or territorial priorities unrelated to climate.

Disincentives

Any number of consequences may be considered by the federal government to discourage weaker climate policy ambition from other orders of government, including:

▶ Backstop mechanism: The federal government could develop a policy response to make up for any gap between initially proposed provincial and federal policies and milestones. This could take the form of a more stringent single policy (e.g., a higher federal backstop carbon price) or a broader package of policies. The backstop could also take the form of a requirement to purchase domestic offsets or international credits (depending on the outcome of international negotiations on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement) that would make up the difference. For instance, Germany is required to purchase E.U. Emissions Trading System credits in the event of a shortfall in meeting its legislated 2030 target.

▶ Consideration of milestones in government decisions: The federal government could enshrine rules in legislation, or through regulation, that require policy- makers to take into consideration milestones and long-term targets in other areas of policy or legislative decision-making. For example, this could be done in relation to assessments of proposed projects within federal jurisdiction. Taking climate change commitments into account in project approval decisions is already part of the scope of the forthcoming Strategic Assessment of Climate Change, which aims to provide guidance on how federal assessments will consider a project’s impact on national GHG emissions. Enshrining long-term targets and interim milestones through a climate accountability framework would therefore ensure that compatibility with these commitments is considered in a project’s assessment.

To conclude this section, Table 2 provides a summary of the trade-offs associated with different options across the three design choices we discuss above.

Table 2: Summary of strengths and weaknesses of options

QUESTION: WHERE DO MILESTONES BIND?

| OPTIONS | STRENGTHS | WEAKNESSES |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusively national level | Provides broad, national direction in meeting climate goals Sidesteps contentious issues of regional or sectoral burden- sharing | Centralizes responsibility for meeting a national milestone to the federal government, potentially downplaying the role of other orders of government |

| Provincial and territorial level | Leads to milestones that reflect the unique economies, GHG emissions profiles, and emissions reduction opportunities across regions Clarifies the level of ambition required at provincial and territorial scales | Directly confronts contentious issues of regional burden-sharing Sacrifices flexibility in meeting national targets (unless there is some sort of regional trading mechanism) |

| Sectoral level | Provides clarity for sectors, a level where key policy decisions are made Avoids directly confronting challenges of regional burden- sharing | Risks raising the overall cost of mitigation since fixed sectoral targets do not respond to shifting emissions reduction opportunities and costs |

QUESTION: WHAT IS THE PROCESS FOR SETTING THE MILESTONE PATHWAY?

| OPTIONS | STRENGTHS | WEAKNESSES |

|---|---|---|

Provinces and territories set their own targets, which in sum define the national pathway | Provides the greatest opportunity for provincial and territorial buy-in Allows ambition to reflect unique regional economies, emissions profiles, and emissions reduction opportunities | Creates risk that the sum of national ambition will be insufficient to meet long-term target |

All orders of government collectively determine the pathway | Creates opportunity for greater buy-in from all orders of government Creates a greater likelihood of pathway being sufficient to meet long-term target | Creates risk of lengthy (or deadlocked) negotiations |

Federal government sets the pathway, based on consultation and engagement | Builds on historical precedence (e.g., setting of 2030 target) Allows different perspectives to be raised and considered | Requires additional time and resources for consultation Risks limiting buy-in from other governments |

Expert advisory body determines the pathway | Sets pathway based on science, expert advice, and Indigenous knowledge Avoids lengthy (or deadlocked) negotiations | Risks limiting buy-in from governments |

QUESTION: WHICH ORDERS OF GOVERNMENT DEVELOP POLICY TO MEET MILESTONES?

| OPTIONS | STRENGTHS | WEAKNESSES |

|---|---|---|

Federal government drives policy | Supports policy certainty by offering a clear policy path for meeting milestones | Leaves a smaller, more reactive role for other governments and reduces their incentive to participate in policy development Limits opportunity to customize policies to reflect regional contexts |

Federal, provincial, and territorial governments contribute to policy development, with federal policy backstop | Builds on existing landscape of federal, provincial, and territorial climate policy Creates potential for greater inter-jurisdictional policy coordination Increases probability of meeting milestones due to presence of a federal backstop | Requires time and resources to facilitate collaboration Relies on willingness of governments to participate in good faith and undertake a collaborative policy- making process |

Provincial and territorial governments drive policy | Sidesteps possible tensions of inter-jurisdictional policy coordination, saving time and resources | Creates the risk that, when taken together, subnational policies will not be sufficiently ambitious to reach national milestones |

- “Historical: 2005 to 2017” and “Projected: 2017 to 2030” annual decline rates are from: Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019. Canada’s 4th Biennial Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Accessed April 12, 2020 from https://unfccc.int/documents/209928.

The “Target: 2017 to 2030” rate is simply the linear decline rate needed to align 2017 GHGs with Canada’s 2030 GHG target of 511 mega- tonnes of CO2-equivalent (Mt CO2-e).

The “2050 Net Zero from 2030 Target” is calculated as the linear decline rate from the 2030 target of 511 Mt CO2-e to “net zero” in 2050. We define, hypothetically and for illustrative purposes only, net zero in 2050 to equal 28 Mt CO2-e. This value is simply the “reductions” currently netted from Canada’s 2030 emission inventory in Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019 (page 27). The 28 Mt CO2-e is comprised of 13 Mt CO2-e Western Climate Initiative Credits and 15 Mt CO2-e of Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry accounting credits

- A federal climate accountability framework could create incentives for provincial action, but it could not compel provinces to adopt as their own the milestones allocated to them under the federal process. As a result, ultimate accountability would rest with the federal government.

- A trading mechanism could act as a solution to this. But although it would create flexibility, a trading mechanism would also likely lead to significant disagreement among provinces and territories. The way in which a national budget was broken out across provinces and territories would strongly affect which jurisdictions were likely end up with surplus credits to sell and to what degree. Provinces and territories would therefore have a strong incentive to advocate for the largest allocation possible, just as they would in the absence of a trading mechanism. So, while a trading mechanism could help reduce overall costs, it would still effectively require the accountability framework to define regional burden-sharing.

- At time of publication, the 100 Mt cap has been legislated but not yet backed up by binding regulations.